Terry Speed: How statistics can help cure cancer

- Published

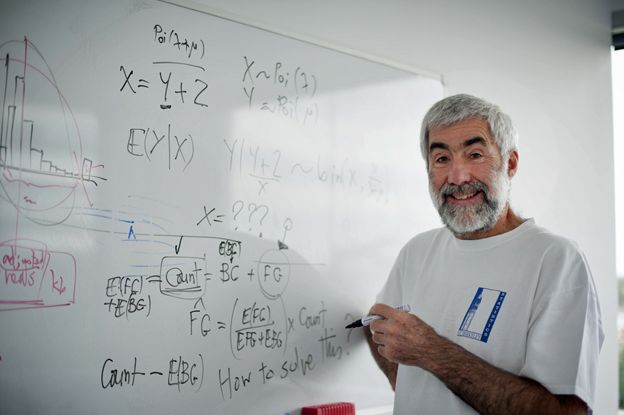

Some of the best minds in medical research are working to understand and one day eliminate one of the world's biggest killers, cancer. But they're not all doctors, chemists, and biologists. Statistics professor Terry Speed has just been awarded Australia's Prime Minister Prize for his big contribution.

Think of cells in the human body as factories. Think of the molecules inside them as machines.

Sometimes that machinery goes haywire - and scientists want to know how and why.

This is how Prof Terry Speed describes the work he's involved in.

New technologies allow a lot of information to be extracted from cells that are not behaving normally.

But huge volumes of data are just that - huge volumes of data - until they are sorted, analysed and interpreted. This is where Speed and his statistical know-how come in.

He's developed mathematical and statistical tools to make sense of all this information and enable biologists to tackle the big questions.

Patterns in the data can then be analysed. How a healthy cell differs from a tumour cell can be seen.

So could it be statisticians in the end who find the cure for cancer?

"I get a little cautious when the word 'cure' comes in," Speed says. "Let's think more in terms of treatment, in terms of focusing what we're doing. What's happening as time goes on is that we're understanding that cancer is more and more diverse, and that there's not going to be one weak spot that you just hit and then you've wiped out all cancers."

Extracting and understanding the information we carry in our bodies means we can be treated as what we are - individuals.

"When a woman has a growth in her thyroid, [with] quite a large number of those growths, you can't tell whether it's benign or malignant just by looking at it. But if you look at the cells, you can see - there's a signature that says 'benign' or 'malignant'."

Previously, if doctors couldn't tell if a patient's tumour was benign or malignant, they would just take it out - better safe than sorry.

"And then this poor woman is not only subjected to surgery, she's on hormone therapy for the rest of her life, because she's lost her thyroid," says Speed, who's head of bioinformatics at the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research.

"Now, if we can study those cells, prevent that unnecessary surgery, this is a great advance. It's not curing cancer but it's making a real contribution."

Are we really talking about a future where a patient who visits a doctor has his or her body analysed by a statistician?

Absolutely, says Speed.

The buzzword, he says, is "personalised medicine".

Until now, if you had a certain type of cancer, you'd be given the same treatment, the same drugs as everyone else who's being treated for that disease. But that's going to change, Speed says.

"We're learning more and more about the idiosyncrasies of tumours and, in particular, how they relate to individuals - because people's own genetic background contributes as well.

"And then as we learn more and more, we can tailor the therapy, the treatment, the drug.

"It's not like you do a big trial where you give half the people one drug, and half the other drug because there's incredible diversity within those halves."

When technological developments in the late 1980s meant that the activity levels of thousands of genes could be assessed simultaneously, Terry Speed was one of the first to get his hands on the data. His analysis techniques are still used in labs all around the world.

Modestly, he says he was just in the right place (Berkeley) at the right time - anyone could have done it. He was just lucky to have the right background - he started out training as a doctor, before switching to maths and statistics - when the technology emerged.

So if the pioneering use of new genetic and molecular technology provided the "right time, right place" opportunity for Speed, and for cancer research, in what other area of dawning possibilities could a young statistician hope to make a mark?

"I've always thought understanding the brain, understanding consciousness," says Speed, aged 70. "If I had another lifetime I think I'd dive into neurobiology, because mental disease - psychiatric disease - is incredibly important in our society. And we're really only scratching the surface of understanding causes of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

"We're just starting to get a lot of imaging data on brains. And the story's got to be there - in the data in the brain."

Follow @BBCNewsMagazine on Twitter and on Facebook